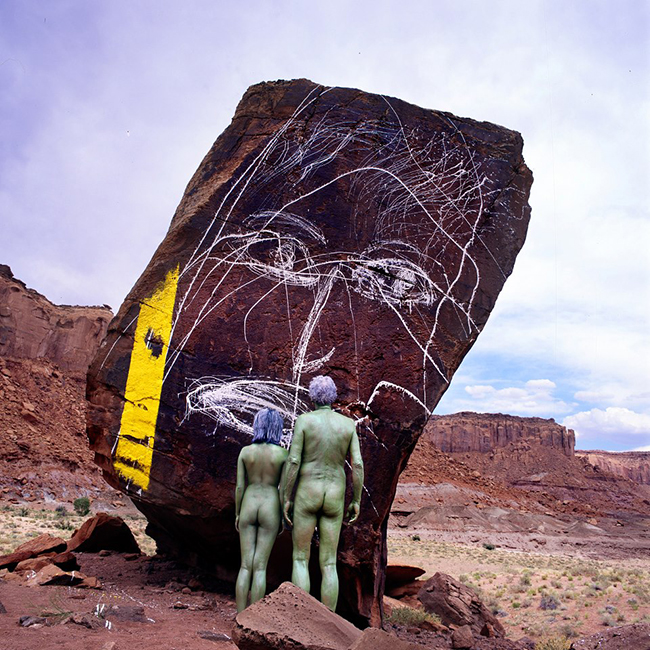

Theater of Life

Jean-Paul Bourdier

Interview by Mackenzie Lowry

Modern day renaissance man Jean-Paul Bourdier creates photography, films, and books that are an ethereal dreamland just beyond plain sight.

Mackenzie Lowry: You were born in France, how did you end up in California?

Jean-Paul Bourdier: I studied in France, and received a scholarship to study in Versailles twice. Later I got my masters degree in Illinois, then I got a job with the University of Georgia Tech, in Atlanta. Afterwards, I got a job for three years in Africa. On return, I got a job with the University at California (Berkeley) where I’ve been a professor since 1982.

Of all these places you’ve lived, do you have a favorite?

Well every place is touching in different ways. Even if I do not like France, I can be touched by the old stones that are Paris. Even if work was very difficult in Africa, I was very touched by the friends I had in Africa and the social life. While I don’t enjoy the social life in America, I do enjoy my work. I do enjoy the view I have of San Francisco and the Golden Gates. Every place has it’s own advantage, flavor and particularities. It’s only my mind that wants to have things perfect.

How did you get into photography?

Coming from a family of photographers, I have denied photography for the longest time, although I have used it in many books on Africa, and in my artwork. Up until the last ten years, I have kept my work quite closed off from the public, so nobody knew what I was doing. Since everyone was a photographer in my family, I didn’t want to be like everybody else – my father, my brother, my grandfather, etc.

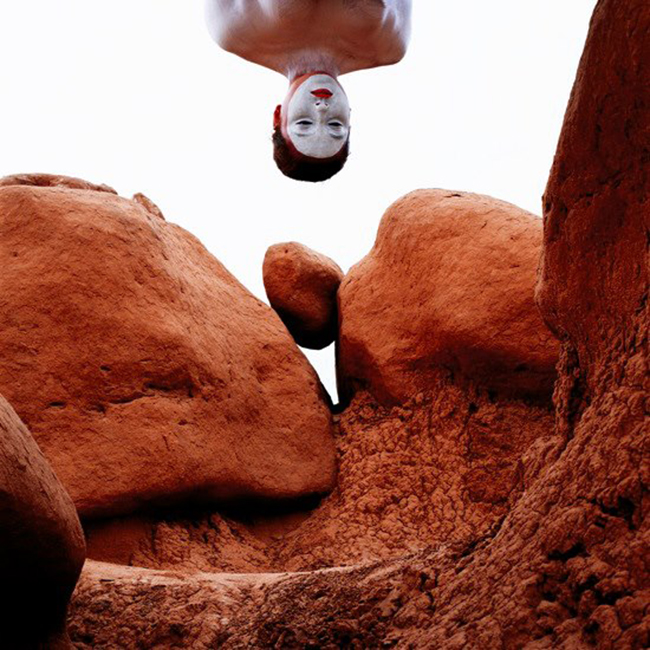

You don’t use Photoshop to create the photos, but are the images completely raw?

I shoot analog film and then we scan the negatives. No, it’s not completely raw. You have to put it in digital form in order to print and share. You have to take off a lot of the dust from the negatives that have been scanned. That’s the degree of Photoshop, but it’s in no way including changes to the content of the photograph.

Do you have any current projects?

Yes, I have two books that are ready to go. One of the books Bodyscapes II: Theater of Life, I recently funded with a Kickstarter campaign. Apart from that, I’m working on a new film about Vietnam that my companion is directing.

What role do you think humans play in affecting the landscape. Are we as active in creating and changing it as the weather or just part of the scenery?

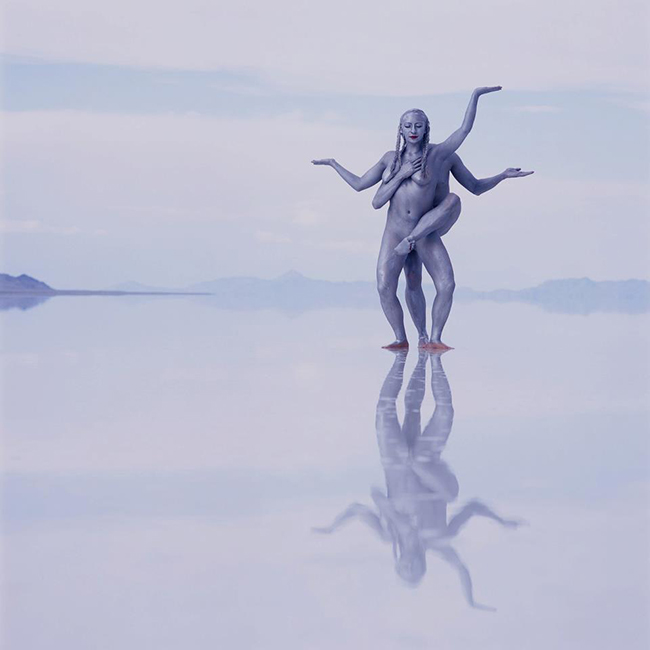

It is really mad of my mind to think that it is somewhat independent from whatever is surrounding it. The activity of my mind is only to separate myself from the environment, in order to dominate it – in order to extract something from it. If I leave my mind on the side and I look at things from just the presence of being, then I realize that there’s absolutely no difference between what is seen and what I am.

Do you think that you can fully capture the landscape in a photo or is there something about being there that you just can’t get?

One of the pretenses of photography is to keep some memory of the experience, but it is actually as ludicrous as trying to bathe in the same water of river twice. The water is gone, everything has gone with it, so you cannot have the same experience twice. Whatever I offer through the photographs is always something separated from my experience. It is offered like a gesture, like a dance if you wish, that could be read in many, many different ways. Do I care about how people interpret it? No I don’t. Do I care about them being inspired, uplifted or amused? Yes, that is an interest of mine, because as in any performance I’m hoping that I will get something out of it, but that something is eluding me.

A lot of your photography is in remote sceneries. Are they shot in Africa?

No, this is all in America. I haven’t returned to Africa since I left work there. I work now only in the desert of the Western US. I have too much luggage with me to be able to travel abroad. To make many of my photographs, one needs quite a bit of gear, but we try to reduce it to something very, very simple.

Do you scout these locations beforehand or do you just venture out in the desert to see what you can find?

Well, it’s both luck and coming back to the same places and rediscovering things fresh and seeing them. Everything has to be approached in the eyes of a 5-year-old or a 20 year-old, who doesn’t know anything and is just saying, “Oh! Oh!” When you go visit someplace, you either visit it with the luggage of knowledge or you don’t. When you don’t, then you see things with freshness without comparing and you can actually enjoy them, whereas if you start comparing you start to be unhappy.

Do you think it’s good for something to shake up what you believe in?

I always say, “Don’t believe what you think”. It’s very useless. It’s useful in that you don’t put your hand on the fire because you know the fire is hot, but beyond these things, the rest is quite useless because every second is new. Even the view I look at is totally different. The clouds have changed, the air is new, the cells of this body have changed. To believe anything is to live in the past, and to deprive myself of living right now. Enjoy the things the now is bringing.

What was your first experience like in Africa?

What seems to be evident in West Africa, like in other parts of the world, is that colonialism may have left, but there is a new form of colonialism that is in place that allows the English, the French, the Americans to sell their products, make money on the back of others under the guise of helping them. To give you an example, the French may help in the literacy project for the schools in some parts of West Africa, but actually, it helps to have people who are literate in terms of reading all kinds of things, so they can later on sell their products with much more ease. Whether they be weapons or such, airplanes or computers, etc.

I will close in saying that what was also very striking was to see that a lot of information that is given is somewhat limited. A man in the computer business says “Well, I’m not telling everybody everything I know, because then I would not have any more justification for beinghere.” That tells you of the self-interest with which we conduct our business in the rest of the world. It’s not just in West Africa, it can be Mexico in relation to America.

Do you think it is a bad thing if they are giving people the skill of literacy?

No, it is not at all, but you see, you have to look at the long-range view. Of course it is wonderful, but everything comes with a an end product. Yes, literacy is good, but it does benefit the very country that is teaching their own language. The French teach French and the Brits teach English, but it mainly benefits them. There are very, very few governmental organizations that teach without self-interest.

Do you have a favorite place you visited in Africa?

First of all, I’m not a city person. I am a person that really loves the rural context – in other words, where people live within the landscape and not within the cityscape. So there are lots of places I would love to visit in Senegal, in Burkina Faso, in Togo, in Benin and rural Kenya. My book Vernacular Architecture of West Africa has really beautiful photographs and drawings of things that are quite unknown to the Western traveler. There are structures that are probably mostly disappeared by now – destroyed by progress and whatever else. I have a lot of fondness for West Africa and would gladly go back if I had enough money to do it.

The unfortunate thing is that, unless things have changed tremendously, it is very hard to travel when you are older, in West Africa. It is very easy when you are young. In the past, were young and we had a lot of difficulties, but those difficulties were small because we were young. As you get older, your health is not as strong. Your resistance to stress is not as strong. So, now we would need more than the shoestring budgets of our youth. We would need money to be able to come back, and to be able to find a hospital if necessary. Which is very hard to find if you are working outside of the cities. If you are in the city, it’s not a big deal.

In your day-to-day experience, do you like to try new things?

The expeditions we do in the desert every year are enough for me. It doesn’t mean that I would not take a vacation somewhere, yes I would. I’m no longer in my 20’s, when I was organizing expeditions in West Africa day in and day out and wouldn’t stop. I’m seeing more now, that there is less need for doing anything.

I don’t have to look anymore for the extraordinary outside of myself. I know it is here within and just at my hands whereas before I would think the further I go, the more interesting it would be.

It’s a little bit like you long to go up the mountain and once you are up the mountain, you realize that living down at the foot of the mountain is really worth it – it’s really all you need. You don’t need to go very far. As a friend in Japan said, “It’s all in the palm of your hand”.

Would you say that the exotic is relative?

Exotic in the sense that we’re looking for ourselves. We think we can go someplace else and discover the self that is more simple, closer to values that are more touching and in tune with the Earth. So, in that sense we tend to exoticise the foreign conscious. The exotic is within us.

When my father was alive, and I didn’t have any relationship with him, but I saw him a couple of times in my life, and he would call me the nomad because apparently I didn’t belong to the French society or other societies. I was moving all the time. You can be a nomad with your own mind, it’s not just the physical life. It is also the life of one’s relationship with one’s mind.

Photos © Jean-Paul Bourdier